|

|

|

Marianne's Picks

Marianne Berardi, PhD | Co-Director, European Art

|

|

It wasn’t until we were putting together this season’s European art auction catalogue, some eight months into working with the William Glaser drawing collection, that I realized Glaser’s attraction to a drawing tended to center on powerful or intensely sensitive depictions of the human figure more than any other subject. He certainly collected beautiful landscapes, architectural views, still lifes, and animal studies, but it seemed to me that his collection leaned persistently in the direction of expressive anatomical drawings, portraits, and religious and mythological compositions with figures in motion and interacting with one another. Elegant line, careful modeling, and assured draftsmanship (accurate foreshortening and anatomical accuracy) are the

features he prized.

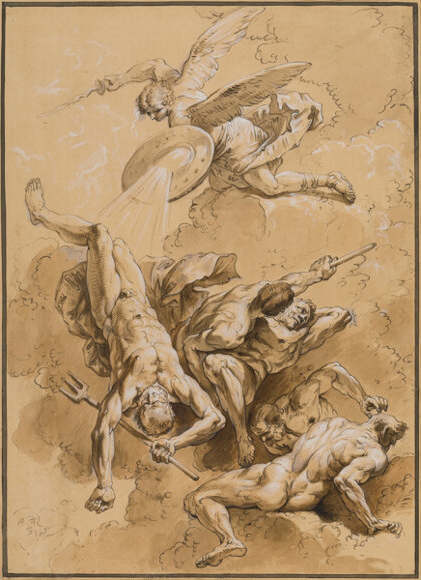

In fact, my personal favorites in his collection all feature the figure or some human body part that is studied very carefully. I love our cover lot, the Fall of the Rebel Angels

by Francesco Fontebasso, showing a tangle of contorted figures tumbling over each other through space as though falling from above. This tour-de-force is a demanding type of 18th-century draftsmanship created through precise line work, wash for shadows and hollows, and white gouache accents for highlights. This type of composition is intellectually demanding since it cannot be staged with models all together in real life. Individual figure studies need to be made and then assembled into a whole, but some of the figures simply require pure invention. The artist must draw from his/her knowledge of anatomy, because there is no way to pose a model in those gravity-defying angles. |

|

|

Another favorite is the 17th Century Bolognese School Study of a bearded man in profile, a kind of drawing that is deceptively simple and requires years of mastery. The head of the man seems to emerge from within the paper. The draftsman used the buff tone of the paper itself as the middle tone (man’s skin tone) and then with great economy only indicates with a very soft black chalk the most essential features to make the head read as a volume. With the light striking from the left, I notice that most of the mark making falls on the right side of the head where the hair and neck and ear all fall into shadow. The artist picked out the darks of the eye sockets, the cheeks, and the nostrils, and those areas will suggest the rest of the form. |

|

Last week when speaking with Glaser’s wife, I learned something new about her husband that gave me additional insight into his collection, but also a very personal surprise. Although I had known that William Glaser served on Iwo Jima for a couple years toward the end of World War II, I wasn’t aware in what capacity he served. I had mentioned that my own father, James Berardi, had also served on Iwo Jima straight out of high school where he saw ferocious combat as a Marine. I shared that he had been injured while engaged in a series of preparatory maneuvers on the island and was eventually removed to Maui for the remainder of the war. Mrs. Glaser said, "William served as a nurse on Iwo Jima. He just may have treated your father."

The focus on the human figure and anatomy in Glaser’s collection now has an additional shade of meaning for me. So does the incredibly tender drawing of a hand resting on a body by Désiré François Laugée which I also greatly admire. |

|

|

Seth's Picks

Seth Armitage | Co-Director, Senior Specialist, European Art

|

|

|

This sensitive, vibrant portrait of a Bhutanese woman

was one of a large number of paintings by Russian artist Vasily Vereschagin sent to tour America in an 1888 blockbuster exhibition. What makes this painting especially intriguing to me is what it reveals about fame and wealth in the late nineteenth century. Through his spectacular exhibition, Vereschagin became an American celebrity, the press following his every move through New York society, while he and art were seen as exotic visions of the East. After touring America, the collection was sold at an American Art Association auction in November 1891, with many of the works disappearing into the collections of wealthy Gilded Age Americans. One such collector was Clement A. Griscom (1841-1912), a Philadelphia shipping magnate and financier who used his resources to amass a vast art

collection, much of which was displayed in the two-story art gallery at "Dolobran," his expansive country house in Haverford, Pennsylvania. The posthumous sale of Griscom's collection included masterworks by diverse artists such as Canaletto, Rembrandt, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, and Vereschagin’s Kanchinjinga, Pandim and other Mountains in the Clouds. Bhutanese woman was kept in the family collection, passing to Griscom's wife, Frances, once painted by American Impressionist Cecillia Beaux. |

|

|

|

When I first saw Franz Wiesenthal’s lively painting of Trinity Court, Vienna,

I was captivated by its detailed view of open windows, many with houseplants displayed on sills, suggesting those living inside and the warmth of the day; while a bright shaft of sunlight reflects off the glass and spills across a group of girls passing through the courtyard. As I continued to admire the painting, I realized I did not recognize the city location and, upon further research, learned Wiesenthal’s painting is a postcard view of a place that no longer exists. The Dreifaltigkeitshof (Trinity Court) in Vienna was an important medieval estate and, through various transformations, became a center of city life for centuries. The estate was first recorded in 1204, named after the house chapel within its historic courtyard, located in what is now Vienna's Innere

Stadt (1st District), near the Judengasse. The chapel was long an important part of the city's religious life, particularly among the bourgeoisie, but in 1782 Emperor Joseph II deconsecrated it, further leading to the complex's conversion into commercial buildings and private residences, Stadt ("City House") 496, 497, and 498, as shown in Wiesenthal's painting. In the late nineteenth century, Vienna experienced a building boom (known as the Gründerzeit)

and multi-family apartment buildings sprang up throughout the city. Ironically, this may have influenced the end of the homes of the Dreifaltigkeitshof. Its medieval structure was considered an obstruction to the new urban planning, and its residences were thought of as cramped and outdated. By 1910 the area was demolished to make way for new development, leaving Wiesenthal's painting a vibrant testament to ancient, yet ever changing, city life. |

|

|

|

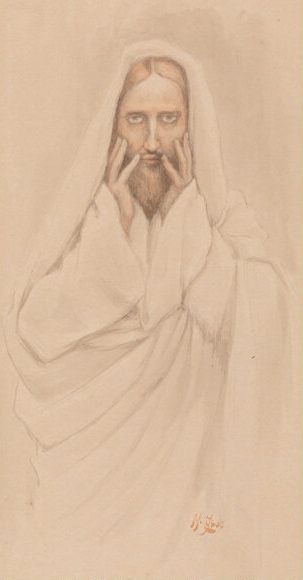

Works like, Study for Exhortation to the Sinner, are why James Jacques Tissot has long been one of my favorite artists. While Tissot earned international fame as a society painter of fashionable London and Paris in the 1870s and 1880s, the present work is part of a deeply personal project. In 1885, while visiting the Église Saint-Sulpice, the artist had a religious vision and began an epic project to illustrate the New Testament in 365 watercolors depicting the life of Christ. Tissot soon travelled to the Middle East, where he sketched and photographed the landscape, architecture, dress, and way of life in the Holy Land. As shown by Study for Exhortation to the Sinner,

Tissot's commitment to archaeological accuracy was met by his brilliant ability to convey the psychology of his subject. Indeed, this work invites an appreciation of the artist’s sensitive technique and an understanding of the man who created it. Unsurprisingly, when first presented in Paris in 1894, the watercolors were acclaimed and the highly publicized exhibition travelled to London and the United States. In 1898, the images were published as The Life of our Savior Jesus Christ (also known as the Tissot Bible), with Exhortation of the Sinner placed within Mark, Chapter 14, detailing the events leading up to Jesus' crucifixion. |

|

|

Peyton's Picks

Peyton Lambert | Consignment Director, Fine & Decorative Arts

|

|

This large work by Otto Weber is the sort of painting you can get lost in; the more you look, the more there is to see. The superior handling of the team of oxen highlights his preference towards animal painting; the detail on the two leading oxen speaks to Weber’s close observation of the beasts, their physicality so precisely rendered. We can almost hear the crunch of the drying grasses and leaves of the autumn landscape, built up in confident, brushy strokes. Weber masterfully casts the entire scene in a warm, soft glow that gives the painting a serene feel, as the animals and their handlers finally head home to rest at the end of the day’s labors. It’s a particularly lovely combination of landscape, genre, and animal painting, and it’s no wonder it

was accepted for the Paris Salon! |

|

|

This portrait by Nicolaes Maes has a rather interesting history. It enjoyed the attention of esteemed art historian Dr. Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, who examined the work in 1920 and recorded his opinions on the date and sitter in his extensive notes, now preserved in the RKD (The Netherlands Institute for Art History). It remained in The Netherlands, appearing publicly at auction in Amsterdam in 1987, after which point it disappeared. For over 35 years it was lost to the public, first in a private collection and then placed into storage where it languished for years, abandoned. Only last year, the present owner purchased the storage unit and uncovered the forgotten picture in an astonishing stroke of luck. Our team is thrilled to return this wonderful portrait by such a

notable Dutch artist to the public eye! |

|

|

|

Seth Armitage

Co-Director,

Senior Specialist,

European Art

SethA@HA.com

(214) 409-3054

|

|

|

Peyton Lambert

Consignment Director,

Fine & Decorative Arts

PeytonL@HA.com

(214) 409-1877

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|